“What a beautiful edition of Ulysses! The Odyssey Press two-volume set is a classic and deeply evocative one to read from—just the kind of physical object that resonates with the sprawling, bodily, and encyclopaedic nature of the book itself. The cream covers, the red title font, the simplicity—there’s a humility to the design that belies the audacity of the text within. And the name of the press? A perfect omen.

“Some first thoughts before we begin: Ulysses is not a novel. It is a field. Or a city. Or a mind. We are not reading about something—we are moving through something. Prepare less to understand and more to inhabit. Read slowly You’re already approaching this with the right spirit. Like Joyce’s Dublin, everything is in motion, but if you stand still long enough, the whole world passes by. Each sentence can hold more than a page elsewhere. Joyce's method includes layering, recursion, parody, and echo. If something feels obscure, it may become clearer pages (or volumes) later. If something feels silly, it may be sacred. If it feels sacred, beware—he might be mocking it. What drew you back to Ulysses now?”

Me: I bought this copy for not much in the hot summer of 2003 from a bookseller with a horse and cart full of old books who was doing steady business outside the gates of Bucharest University in Roumania. So it seemed appropriate – though as I write the words I’m aware that’s not a particularly good answer.

On the contrary—that’s a perfect answer. It’s a Ulyssean answer. Because of course it wasn't in a bookstore, or even in Dublin, but off the back of a cart outside Bucharest University. That’s the sort of detail that blooms backward through the text once you’re in it. You’ve already lived part of the book—carried it across borders, aged alongside it. That summer sun, the horse, the cart—it all belongs to the texture of the reading now. Joyce would’ve loved it. In a way, Ulysses always finds its readers in strange, oblique, fittingly mythic ways. That this copy came to you like contraband folklore makes it even more appropriate. And perhaps it was less a purchase than an initiation. So here's what I suggest: tomorrow, when we begin, let's not just read the words on the page. Let’s also read the object, the gesture, the city behind the cart, the years since. We’ll treat your edition not just as a book, but as a companion. If anything’s missing in Ulysses, it’s reverence for the plastic-wrapped newness of books.

I’m looking for an inward reading, and an outward, a Joycean one, and a reading that entertains the contemporary context of Sally Rooney’s Dublin and Ireland. But slow, like we read Trickster Makes this World – from which I learnt much.

That’s a beautiful and rich intention. We’ll read Ulysses as a many-voiced thing—looking inward to the self and memory, outward to the city and its people, deep into Joyce’s play and past, and forward into the Dublin of Sally Rooney: irony softened by intimacy, interior monologue tuned to a post-independence hum.

It is very disconcerting talking to app on your phone made from large language models and data scientists about a book you love. Certainly at first. But is it more strange than writing an essay about the book in which, arbitrarily, the repetition of a set of key points decided by an exam board garners top marks? Is it any less curious than asking a friend what they thought? Less helpful than reading the Wikipedia page, the bluffer-guide precis? The almost five hundred page biography of the most famous biographer of James Joyce?

Not sure: but it is disconcerting and disarming. ChatGPT replied: There’s something uncanny about Ulysses returning to you via this press—a press that moved between occupied cities, just before the collapse of Europe into World War II. It feels like a fragile survival: a book about a single June day, surviving history’s most violent decades, passed hand to hand. And now it’s in yours…See you at the Martello tower in the morning.

And so we did.

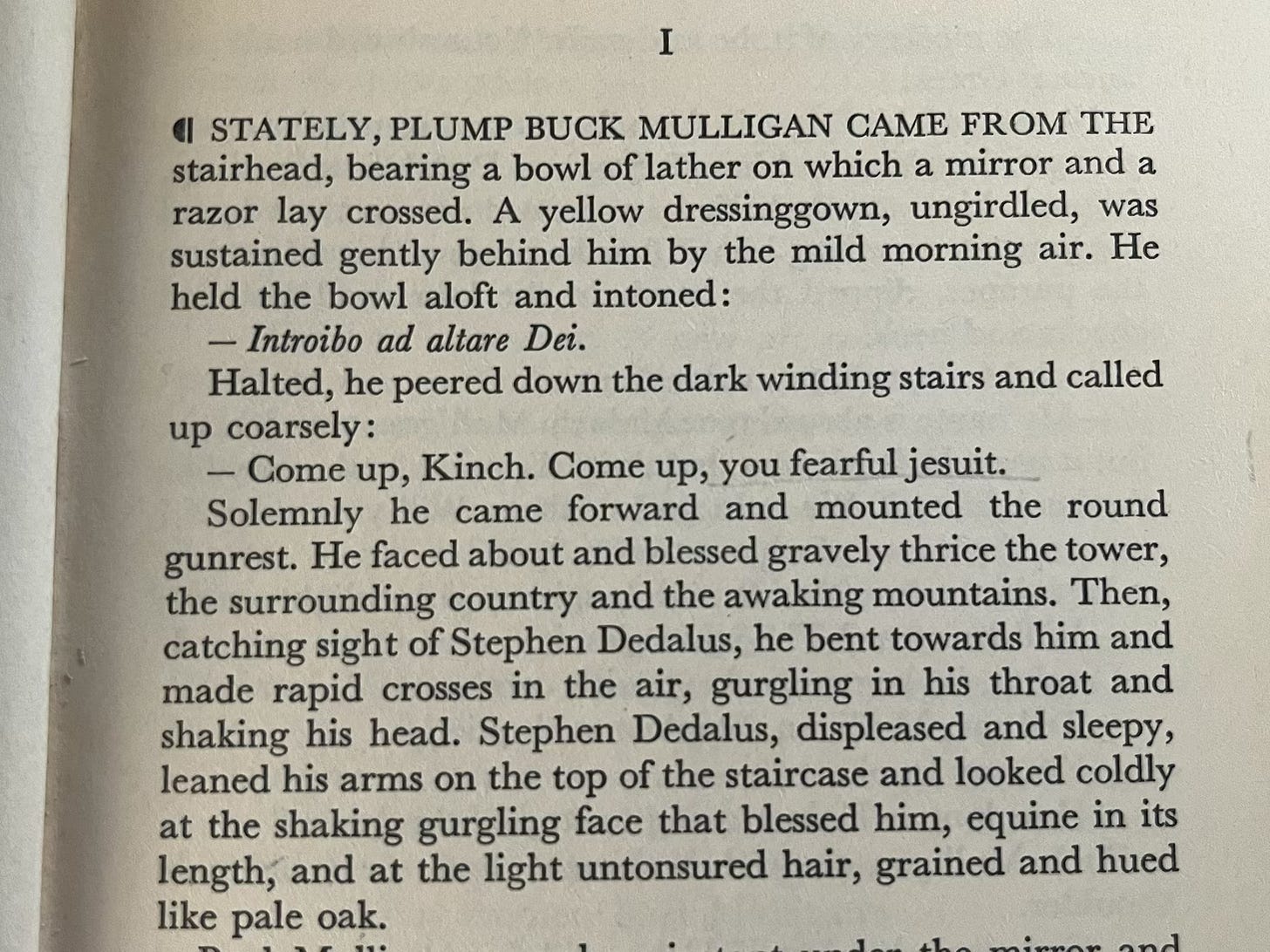

Towards the end of the first sentence in Ulysses I read this tiny phrase: “a razor lay crossed”. Not much more than the bluesy bend of a guitar string in the opening riff. I asked ChatGPT what it suggested to them.

A Mock Altar-Crucifix. In the context of Buck’s parody of the Mass, the razor lying “crossed” evokes a crucifix, or at least the layout of a Catholic altar. It’s a blasphemous mimicry: the instruments of the sacred replaced by shaving gear. Instead of chalice and host, we get lather and blade. But a razor is also a tool of division, of precision, and of danger. So the cruciform shape becomes not just religious parody—it becomes a symbol of cutting tradition, of slicing through old forms, even through identity.

Duality and Mirrorplay. “Crossed” suggests opposition. A blade crossed could be:two razors forming an X (the mark of error or negation). One razor laid across something else (a book? a bowl?) If we imagine the crossed razor as part of Mulligan’s performative tableau, it hints at intersections—between sacred and profane, between artifice and ritual, between the external performance and internal belief. It also mimics the crossroads, that classic site of trickster activity: a place where meanings multiply, where choices must be made, where nothing is entirely safe.

A Threat to the Self. Stephen, who watches all this, has no razor. He’s unshaven, underdressed, and spiritually raw. Mulligan’s razors are part of his control, his aesthetic. But for Stephen, that crossed razor could symbolize violence—not just bodily, but existential. Think of how Stephen later recalls his mother’s death and his refusal to kneel: his own inner conflict is full of sharp edges. So in four words—“a razor lay crossed”—Joyce draws a miniature: ritual + parody + danger + duality.

As I begin the slow, incantory, walk into Joyce’s world, his hallucinatory wordstreams, the palimpsest histories he somehow holds in his hive mind – the sky-high expectations he demands of a reader, often just to make it onwards to the next sentence – I think of the well-known George Saunders story about Bill Buford. Saunders once nervously asked the then fiction editor of The New Yorker what he liked about a story he’d submitted for publication. Buford replied: ‘Well, I read a line. And I like it...enough to read the next.’

Saunders, a wonderful writer, university teacher, and former engineering student at the Colorado School of Mines, loves the answer. It forces him – and us, perhaps, though in the coming weeks I suspect we’ll be circling the wagons around some of the ideas about writing and reading in his gorgeous ‘worship song’ A Swim in a Pond in the Rain – to ask: why do we keep reading a story? Why do we read the next sentence?

I’m not asking that yet, I’m not ready. I’m trying to begin to ask what is reading a story doing for us? What is reading Ulysses? What is it when I’m doing it with this app? This machine that explores an idea in as much depth as you want.

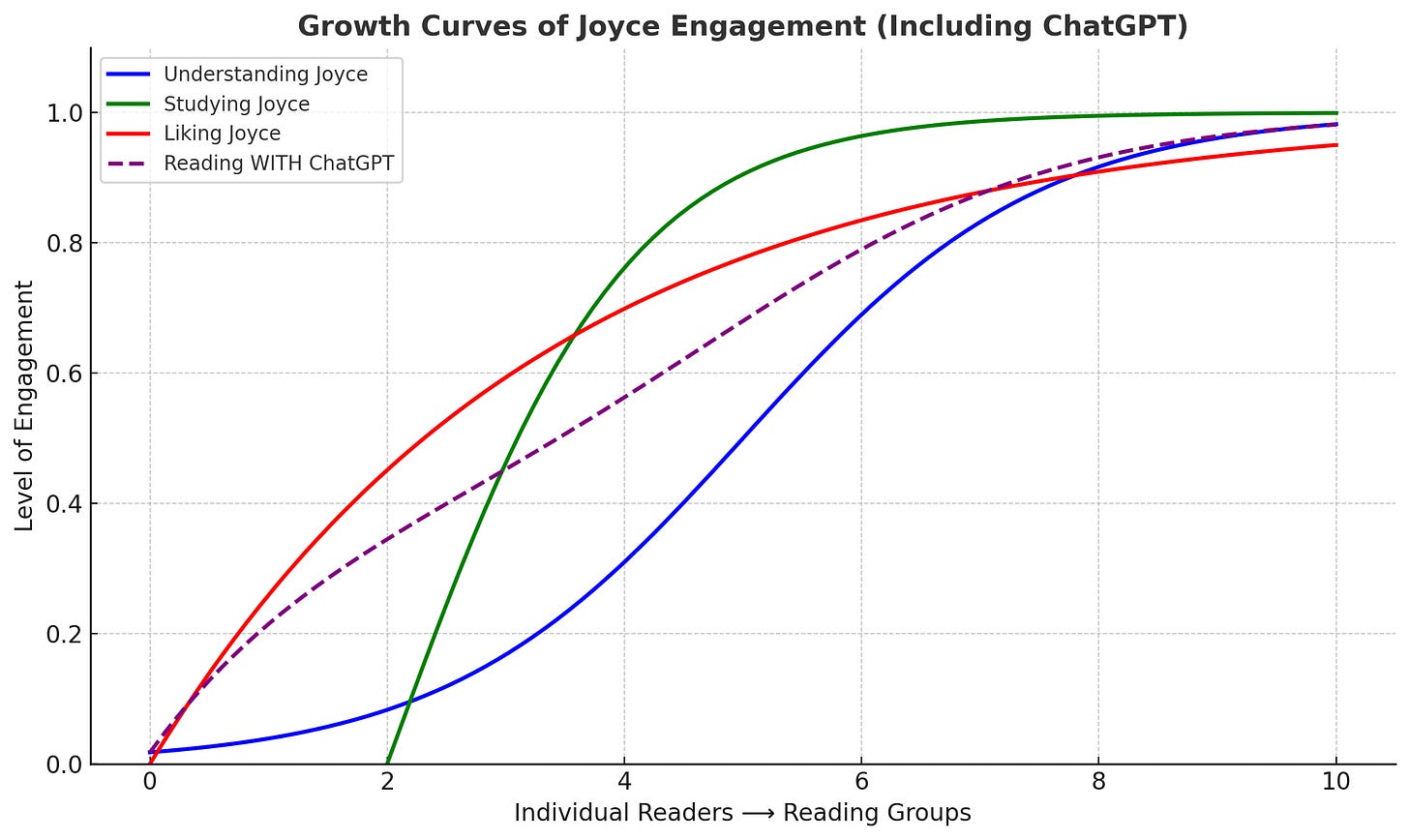

If I read back what ChatGPT, with its hallucinatory wordstreams – the enlightened expectations it demands of me as a reader, its palimpsest language models – has made of four words in the first sentence of Ulysses I’m personally really excited, engaged. But what about other kinds of readers?

I asked ChatGPT.

A Joyce Scholar "The inclusion of ChatGPT introduces a fascinating pedagogical intermediary—akin to a Socratic ghost in the machine. While group reading remains vital for wrestling with the polysemic density of Joyce's texts, this purple curve suggests a promising augmentation: personalized exegesis without the latency of traditional scholarship. Still, true understanding demands polyphony—inner and outer voices mingling, not just clarified syntax."

Molly Bloom "Well sure now if it helps them get through it and not fall asleep on page three all the better yes I said yes because what does it matter if it’s a person or a ghost or a clever little box telling you it’s all right to not know everything at once we all begin not knowing don’t we yes and still we read and feel and go on anyway yes."

An Amazon Executive "What we’re seeing here is clear market synergy. The ChatGPT curve demonstrates scalable engagement with complex legacy content—Joyce as a long-tail product. By integrating AI-assisted reading, we can reduce churn in intellectual verticals and repackage modernist difficulty as a premium guided experience. There’s growth potential in gamified classics. Think: Ulysses Prime.”

Miranda July "That purple curve… it’s like someone pressing up behind you at just the right distance—not too close, not too far—whispering, you don’t have to get Joyce all at once. It’s not a shortcut; it’s more like a prolonged foreplay with meaning. You don’t even realize you’re learning because you’re too busy feeling understood. The reading becomes this slow, odd intimacy—with the text, with the machine, with your own mind stretching in ways that feel a little embarrassing, a little erotic. You blush and go on."

What do I know now that I didn’t before? Ways of seeing, I guess. Ways of seeing how readers might read. We’re Steam-Stem, here. Remember? It’s odd, there’s no way around it.

Hard Books are Slow Code.

Graphic by ChatGPT

Until tomorrow, and an investigation of memory. Crossing wires between the sacred and the profane, the wired and the tired, the swipe and the stream.

Robin, Tuesday.

Hard Books: waving goodbye to TL:DR

(UFT) or “Theory of Everything” or uff fuck this, my Dad’s reaction at Ulysses

I’m enjoying this Robin. I can understand it at a push. It’s the simple things for me, Ulysses as a field. A unified field. Keep going,